On January 12, 2026, Singapore’s Parliament passed the Health Information Bill, legislation that will fundamentally reshape how patient health data flows through the country’s healthcare system. For privacy practitioners, this development represents one of the most significant departures from consent-based data protection frameworks seen in any developed democracy.

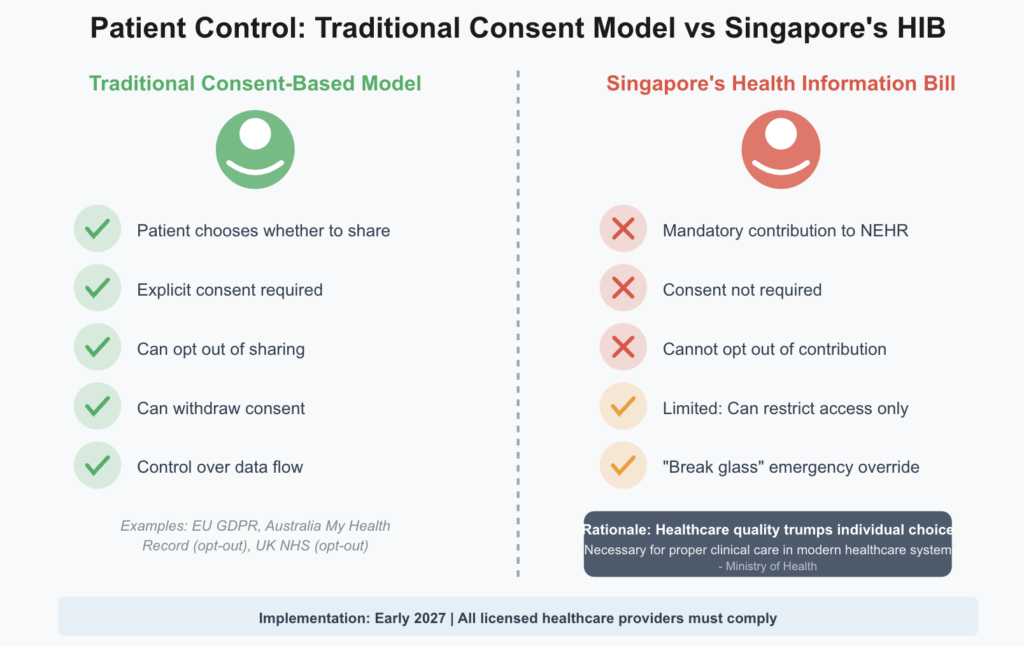

The new law does something remarkable and controversial: it eliminates patient choice about whether their health information enters a national database. Starting in early 2027, every licensed healthcare provider in Singapore—from major private hospitals to neighborhood general practitioner clinics—must contribute key patient health information to the National Electronic Health Record system. Patients cannot opt out. Their consent is not required. The Ministry of Health has determined that comprehensive data sharing is simply necessary for proper clinical care in the modern era.

This article examines what the Health Information Bill means for privacy law, why Singapore has chosen such an aggressive approach, and what compliance challenges healthcare organizations will face over the next year.

The Problem Singapore Is Trying to Solve

To understand why Singapore has taken this path, you need to understand the demographic transformation underway. By 2030, one in four Singaporeans will be aged 65 or older. This aging population faces rising rates of chronic disease requiring sustained, coordinated care across multiple providers over many years.

Singapore’s healthcare system has responded by shifting care delivery from acute hospitals into community settings through national programs like Healthier SG and Age Well SG. Patients now routinely receive care from a sprawling network of providers: their regular GP, multiple specialists, community hospitals, dialysis centers, home medical services, laboratories, radiology clinics, and dental practices. Each interaction generates health information critical to safe, effective treatment.

The fragmentation creates real clinical risks. A patient might see a cardiologist who prescribes a new medication, then visit their GP the following week with a different complaint. If the GP doesn’t know about the cardiologist’s prescription, they might prescribe something that interacts dangerously with the first medication. A patient allergic to penicillin might receive it in an emergency room because the treating physician has no access to their allergy history. Someone might undergo duplicate imaging tests because their new specialist can’t see that the same scan was performed three months earlier at a different facility.

The National Electronic Health Record system was established in 2011 to solve these problems by creating a centralized repository of key health information accessible to all treating physicians. But there was a critical limitation: participation by private healthcare providers was voluntary. As of late 2024, only about 30 percent of private providers were contributing to NEHR. The result was a fragmented system that defeated the purpose of having a national health record in the first place.

The Health Information Bill eliminates that fragmentation by making participation mandatory. Every licensed healthcare provider must contribute. Every patient’s information must be included. The voluntary era is over.

What Information Gets Shared

The Health Information Bill requires healthcare providers to contribute what the Ministry of Health terms “key health information” to NEHR. This includes allergies, vaccinations, diagnoses, medications prescribed, laboratory test results, radiological images, and discharge summaries from hospital stays.

This is not a complete medical record. The detailed clinical notes a doctor writes during a consultation, for instance, are not required to be in NEHR. The focus is on information that other healthcare providers would need to know to treat the patient safely and effectively. A doctor needs to know what medications you’re taking and what you’re allergic to, but they may not need your physician’s detailed assessment notes from every appointment.

The distinction matters because it affects the scope of information that flows through the centralized system. Healthcare providers will maintain their own detailed clinical records, but they must extract and contribute the key elements to NEHR. This creates a two-tier information architecture: comprehensive local records at each provider, and a shared record of critical information accessible across the system.

Beyond the core NEHR contribution requirement, the Bill also establishes a framework for sharing health information held outside NEHR through Ministry of Health-approved data sharing arrangements. This sharing is permitted only for specific purposes: outreach under national health initiatives, supporting continuity and coordination of care, determining eligibility for health-related financing schemes, and providing proactive support for vulnerable individuals who may benefit from interventions.

The Agency for Integrated Care already shares data with community care providers to enable befriending services for vulnerable seniors. The Health Information Bill provides an additional legal basis for such activities and expands the scope for proactive community health interventions. This secondary sharing framework operates separately from the main NEHR contribution mandate and involves case-by-case ministerial approval.

The Consent Problem

For privacy lawyers trained in frameworks that center individual consent as the primary basis for data processing, the Health Information Bill presents a fundamental challenge. The legislation simply does not ask for patient consent to contribute their health information to NEHR. It mandates contribution regardless of patient preferences.

This represents a significant departure from the consent-heavy approach seen in frameworks like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, which generally requires explicit consent for processing health data absent another legal basis such as vital interests or public interest. The Health Information Bill appears to rely primarily on a public interest rationale grounded in healthcare quality and patient safety.

The Ministry of Health’s position is straightforward: comprehensive health information sharing is necessary for proper clinical care in a modern healthcare system where patients routinely receive treatment from multiple providers. Making participation voluntary defeats the purpose because gaps in the record create the very risks the system is designed to prevent. Therefore, patient consent is irrelevant. The question is not whether patients want their information shared, but how to share it safely and appropriately.

This philosophical stance puts Singapore’s approach at odds with privacy frameworks that treat individual autonomy over personal data as a fundamental right. The Health Information Bill effectively determines that healthcare quality is more important than individual choice about health information sharing, at least within the domestic healthcare system.

The legislation does provide some mechanisms for patient autonomy, but they operate within strict constraints. Patients can use the HealthHub mobile application to place access restrictions on their NEHR records so that only selected healthcare providers can view their information. This gives patients some control over who accesses their data, even though they cannot prevent the data from being contributed to the system in the first place.

However, even these access restrictions have limitations. A subset of critical information—specifically allergies and vaccination records—remains accessible to all healthcare providers regardless of any access restrictions the patient has placed. The rationale is that this information is so critical to safe prescribing and treatment that it cannot be hidden, even from providers the patient has not specifically authorized.

Additionally, the Bill includes what’s known as a “break glass” provision. In medical emergencies, doctors can activate this feature to access a patient’s complete NEHR record despite any access restrictions the patient has placed. This ensures that emergency physicians can access potentially life-saving information when seconds count. But it also means that patient access restrictions can be overridden unilaterally by treating physicians when they determine an emergency exists.

The break glass provision is relatively common in electronic health record systems internationally, but it remains controversial from a privacy perspective. It effectively makes patient control mechanisms advisory rather than absolute. A patient can restrict access to their records, but they cannot prevent access in circumstances that a treating physician determines require it.

The Sensitive Health Information Carve-Out

The Health Information Bill recognizes that not all health information carries equal privacy implications. The legislation provides for special handling of what it terms “Sensitive Health Information,” though the exact definition and scope await regulatory clarification.

Based on consultation documents, Sensitive Health Information will not be as readily accessible as other key health information in NEHR. The intention is to mirror current clinical practice where certain types of information are limited to medical practitioners, selected nurses, and pharmacists rather than being visible to all healthcare staff.

While the specific categories of Sensitive Health Information have not been formally defined in regulations, the consultation process suggests this will likely include information about mental health conditions, HIV status, genetic information, reproductive health, and other particularly sensitive categories. The more restricted access model for Sensitive Health Information acknowledges that while comprehensive sharing serves important healthcare purposes, some information requires additional protections given its potential for stigma or discrimination.

This carve-out creates a two-tier access model within NEHR: standard key health information accessible to all treating healthcare providers, and Sensitive Health Information accessible only to a more limited subset of providers with appropriate clinical justification. The implementation details of this distinction will be critical, as they will determine how effectively the system balances comprehensive information sharing with appropriate privacy protections for the most sensitive data.

Relationship with Existing Privacy Law

A critical question for practitioners is how the Health Information Bill interacts with Singapore’s existing Personal Data Protection Act of 2012. The relationship is one of coexistence and layering rather than displacement. The Health Information Bill creates sector-specific obligations that operate alongside PDPA requirements rather than replacing them.

This means healthcare providers must comply with both frameworks simultaneously. The Health Information Bill does not override PDPA obligations; instead, it adds health-specific requirements on top of the existing data protection baseline. Where the two frameworks overlap, both must be satisfied. Where they address different aspects of data handling, both apply to their respective domains.

The practical implications are significant. Organizations must carefully map their data flows to determine when health information-specific rules apply and when PDPA safeguards continue to govern. A single data breach may trigger multiple notification obligations under different legal frameworks. Compliance with one regime does not discharge duties under another. This layering creates substantial compliance complexity for healthcare organizations, which must maintain familiarity with both frameworks and ensure their practices satisfy both sets of requirements.

For privacy lawyers advising healthcare clients, this means compliance assessments cannot simply focus on the Health Information Bill in isolation. A comprehensive compliance program must address both HIB requirements and PDPA obligations, mapping out where they intersect and where they impose independent duties. The healthcare organization needs policies and procedures that address the union of both frameworks, not just one or the other.

Cybersecurity and Breach Notification

The Health Information Bill imposes comprehensive cybersecurity and data security obligations on all persons who contribute to, access, or use the NEHR system. These requirements extend beyond electronic safeguards to encompass physical and organizational measures.

Healthcare organizations must implement technical safeguards including frequent and timely updates of systems and software, anti-malware and anti-virus solutions, encryption of health information during transmission and storage, and multi-factor authentication for system access. Organizational safeguards include staff training on cyber-hygiene practices, personnel awareness of confidentiality and integrity responsibilities, and regular audits to flag inappropriate access. Physical safeguards protect both electronic and non-electronic health information and ensure proper disposal procedures to prevent unauthorized access.

The legislation also requires business continuity capabilities, including the ability to withstand service disruptions and regular checks on corporate policies and processes. These requirements reflect a comprehensive approach to information security that addresses technical, human, and process dimensions of protecting health data.

The breach notification requirements are particularly stringent and operate in addition to existing PDPA notification obligations. Healthcare organizations must notify the Ministry of Health within two hours upon confirmation that an incident is notifiable. Separate notifications to the Personal Data Protection Commission remain required under PDPA for breaches that meet that framework’s notification thresholds. Affected individuals must be notified for breaches involving Sensitive Health Information.

The two-hour notification window to the Ministry of Health is among the most aggressive breach notification timelines globally. Most data protection regimes allow 72 hours or more for breach notification to regulators. Singapore’s requirement reflects the healthcare sector’s status as a prime target for cyberattacks and the critical importance of rapid response to limit impacts on patient safety and privacy.

The rationale for this aggressive timeline is that prompt notification allows the Ministry of Health to take immediate action to limit damage, coordinate response efforts across affected organizations, and detect patterns that might signal larger-scale attacks. Singapore’s Cybersecurity Agency reportedly receives reports of ransomware cases affecting the healthcare sector every three days, highlighting the sustained threat environment.

However, the two-hour requirement creates significant practical challenges. Healthcare organizations must have robust incident detection and escalation procedures to meet this timeline, particularly outside normal business hours. The organization needs clear protocols for determining when an incident is “confirmed” as notifiable, rapid escalation channels to senior decision-makers, and pre-established communication links with the Ministry of Health.

An important limitation in the breach notification framework is that the Health Information Bill does not directly impose obligations on third-party vendors such as providers of clinical management systems and cloud storage services. Instead, the onus lies on healthcare providers to ensure their engagement of such vendors complies with HIB requirements. Healthcare organizations bear full responsibility for vendor compliance, which means contractual arrangements with vendors must explicitly address Health Information Bill obligations and vendor due diligence becomes critical. This approach creates potential gaps if vendors are inadequately supervised or if contractual language fails to adequately allocate responsibilities.

The Derived Information Framework

Beyond direct clinical care, the Health Information Bill establishes a framework for using what it terms “derived information” generated from NEHR data for secondary purposes. This framework addresses research, public health surveillance, health system planning, and other uses beyond treating individual patients.

The legislation distinguishes between two types of derived information. Type 1 derived information is identifiable—it can be linked back to specific individuals. Type 2 derived information is anonymized and cannot be traced to particular persons. The two types face different approval standards reflecting their different privacy implications.

Type 1 derived information may be approved by the Minister for Health if the application relates to or promotes public health. In considering such applications, the Minister will evaluate whether it would be feasible to obtain consent from the affected individuals and whether the intended purpose could be achieved with anonymized data instead. This creates a preference for consent where practical and anonymization where possible, while allowing exceptions where neither is feasible but public health benefits are clear.

Type 2 derived information may be approved if determined to be in the public interest. The lower threshold for anonymized data reflects the reduced privacy risk when information cannot be linked to individuals. However, the Minister may substitute Type 2 for Type 1 if the applicant’s stated purpose can be adequately met with anonymized data, creating an incentive to prefer privacy-protective approaches.

This framework appears designed to balance research and public health needs against privacy protection while giving significant discretion to the Ministry of Health. Rather than creating rigid rules, it establishes principles—prefer consent, prefer anonymization, require public interest justification—and delegates case-by-case determinations to ministerial judgment.

The framework raises questions about transparency and oversight. Will the criteria for approval be published? Will there be public reporting on what derived information applications are approved? Will there be independent review or appeal mechanisms for rejected applications? Will approvals be time-limited or permanent? These implementation details will significantly affect how the framework operates in practice.

Enforcement and Penalties

The Health Information Bill establishes criminal penalties for violations, with penalty levels aligned to comparable provisions in other Singapore statutes. Penalties for unauthorized access to NEHR, improper disclosure, and misuse of NEHR health information are aligned with penalties under the Computer Misuse Act. Penalties for organizational failures to meet cybersecurity and data security requirements are similarly aligned with penalties in related legislation.

A particularly important provision specifies that individual consent is not a defense to improper access, collection, use, or disclosure of health information. This underscores that patient consent cannot override the statutory framework’s access limitations and purpose restrictions. Even if a patient has consented to a particular disclosure, if that disclosure violates the Health Information Bill’s requirements, it remains unlawful and subject to penalties.

This provision reflects a fundamental principle of the legislation: that health information handling is governed by statutory rules designed to protect systemic integrity, not by individual contracts between patients and providers. Patient consent may be relevant in some contexts, but it cannot authorize violations of statutory restrictions.

The Ministry of Health will have broad regulatory oversight powers including approving data sharing arrangements for non-NEHR information, determining what constitutes public interest for derived information use, establishing technical and operational standards for NEHR contributors, investigating breaches and compliance failures, and imposing sanctions for non-compliance. These powers give the Ministry substantial discretion in how the framework operates in practice.

Privacy Concerns and Civil Society Response

While the Ministry of Health emphasizes the healthcare benefits of comprehensive data sharing, privacy advocates and civil society organizations have raised several concerns about the Health Information Bill’s approach.

Critics argue that the mandatory sharing requirement fundamentally changes the doctor-patient relationship. Historically, patients could expect that information shared with one healthcare provider would not automatically flow to all others without their knowledge or consent. The Health Information Bill makes comprehensive sharing the default, eliminating patient choice about whether their information enters a national database.

Some worry this could create a chilling effect on healthcare seeking. Patients might avoid seeking care for sensitive conditions—mental health issues, sexual health concerns, substance abuse—if they know the information will be automatically shared across all their healthcare providers. While the Sensitive Health Information carve-out is intended to address this concern, its effectiveness depends on implementation details that remain unclear.

Critics also argue that the patient control mechanisms provided in the legislation are insufficient. The fact that critical information like allergies and vaccinations remains accessible even with access restrictions, combined with the break glass emergency override provision, means patient control is quite limited. Patients can express preferences about access, but they cannot effectively prevent access when the system or treating physicians determine it is needed.

The framework for non-NEHR data sharing and derived information use raises concerns about function creep. While currently limited to specified purposes with ministerial approval required, critics worry about gradual expansion of permissible uses over time. The broad discretion granted to the Minister for Health in approving derived information applications creates potential for scope expansion without additional legislative oversight.

Finally, centralizing comprehensive health information for an entire nation’s population creates an attractive target for cyberattacks and potential state surveillance. While the Health Information Bill imposes robust security requirements, no system is impenetrable. A successful attack on NEHR could compromise the sensitive health information of millions of Singaporeans simultaneously. The concentration of data in a single system magnifies both the attractiveness of the target and the potential damage from a successful breach.

The Ministry of Health has defended its approach by emphasizing that healthcare quality and patient safety must take priority. The fragmentation of health records created by voluntary participation posed real clinical risks that have likely resulted in preventable adverse events, medication errors, and duplicative testing. The Ministry’s view is that mandatory comprehensive sharing is necessary to deliver high-quality coordinated care in a modern healthcare system, and that this public interest outweighs individual privacy preferences about information sharing within the healthcare system.

This reflects a broader philosophical difference about the balance between individual autonomy and collective welfare. The Health Information Bill represents a policy decision that healthcare system effectiveness is more important than individual choice about health information sharing, at least in the domestic clinical care context.

International Comparisons

Singapore’s approach can be understood in the context of electronic health record initiatives in other jurisdictions. Many countries have implemented or are developing centralized or federated electronic health record systems, but Singapore’s mandatory approach is more comprehensive and prescriptive than most comparable systems.

The United Kingdom’s NHS Digital infrastructure includes integrated care records, but patients can opt out of having their information shared beyond their immediate care team. Australia’s My Health Record system initially launched with an opt-in model, then shifted to opt-out after concerns about low uptake, but still allows patients to refuse participation entirely. Estonia has built a sophisticated nationwide e-health system, but it includes patient control mechanisms and explicit consent requirements for most uses.

The United States has no unified national electronic health record system. Instead, it has pursued interoperability standards and incentives for providers to adopt electronic health records that can communicate with each other, but participation is not mandated and the system remains highly fragmented.

Singapore’s model is distinctive in eliminating patient choice about contribution to the national record. The closest international parallel might be countries with nationalized healthcare systems where health records are maintained by the public health service, but even in those contexts, patients typically have some ability to restrict access or request that certain information be withheld from shared records.

The aggressive two-hour breach notification requirement is also unusual internationally. Most data protection regimes allow 72 hours or more for breach notification to regulators. Singapore’s much shorter timeline reflects both the high threat environment facing healthcare systems and the government’s emphasis on rapid response capabilities.

The derived information framework is noteworthy for its explicit structure and ministerial approval process. Many jurisdictions have less clear frameworks for secondary uses of health data, relying on general public interest or research exceptions in data protection law rather than sector-specific approval processes. Singapore’s approach provides more clarity about permissible uses and approval criteria, though it also concentrates significant discretion in the Ministry of Health.

Compliance Challenges and Timeline

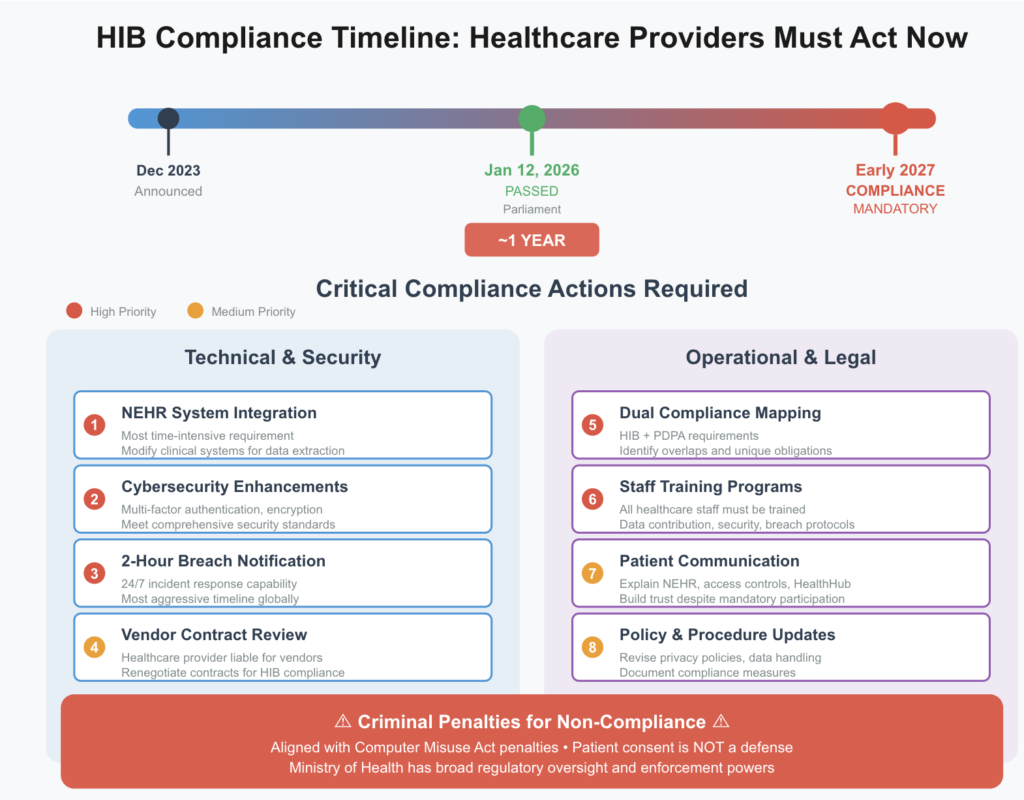

Healthcare organizations face significant compliance challenges as the Health Information Bill moves toward implementation in early 2027. The approximately one-year timeline from passage to implementation is relatively aggressive given the scope of changes required.

The most time-intensive requirement is technical system integration with NEHR. Healthcare providers who are not currently contributing to NEHR will need to modify their clinical information systems to extract required data elements, format them appropriately, and transmit them securely to the NEHR infrastructure. This requires understanding the technical specifications, modifying software systems, testing the integration, and potentially training staff on new workflows. For smaller practices without dedicated IT staff, this may require engaging external consultants or vendors.

All nine private hospitals in Singapore have committed to NEHR integration by 2025, providing some advance movement, but thousands of smaller clinics and practices will need to achieve integration over the coming year. The Ministry of Health will need to provide clear technical specifications, potentially reference implementations, and support resources to enable widespread successful integration.

Cybersecurity enhancements may be required for many organizations to meet the Health Information Bill’s comprehensive security requirements. Organizations will need to assess their current security posture against the legislation’s standards, identify gaps, and implement necessary improvements. This might include deploying multi-factor authentication, enhancing encryption capabilities, strengthening access controls, implementing more sophisticated monitoring systems, and enhancing business continuity capabilities.

Breach notification procedures must be revised to accommodate the two-hour notification requirement to the Ministry of Health. This requires clear incident detection and escalation protocols, 24/7 capability to assess incidents and make notification decisions, pre-established communication channels with the Ministry of Health, and regular testing through exercises or simulations. Organizations accustomed to the more relaxed timelines in typical data breach notification regimes will need to significantly accelerate their response capabilities.

Vendor agreements require review and likely renegotiation to address Health Information Bill compliance. Healthcare organizations need to ensure their contracts with clinical management system vendors, cloud storage providers, IT services firms, and other third parties clearly allocate responsibility for HIB compliance, impose security requirements meeting HIB standards, establish breach notification obligations, and address liability for HIB violations. Given that the legislation places responsibility for vendor compliance on the healthcare organization, not directly on the vendor, careful contracting is essential.

Staff training programs need development and deployment. Healthcare staff must understand what information needs to be contributed to NEHR, how to use systems for contribution, security requirements and cyber-hygiene practices, breach notification procedures and escalation protocols, and patient questions about NEHR and access controls. This training must be delivered to all relevant staff before implementation.

Patient communication strategies should be developed to explain the changes. While the legislation does not require patient consent, healthcare organizations will benefit from proactively communicating with patients about what information will be shared via NEHR, who can access it, how to use access restrictions in HealthHub, how to monitor who accesses their records, and what the emergency override provision means. Clear, accessible communication can reduce patient anxiety and build trust even in a mandatory system.

Organizations should also conduct comprehensive compliance assessments that map current practices against Health Information Bill requirements and identify gaps. This assessment should cover data contribution capabilities, cybersecurity posture, breach notification procedures, staff training status, vendor management, and patient communication readiness. The assessment provides a roadmap for compliance efforts and helps prioritize resources.

Unanswered Questions

Several aspects of the Health Information Bill’s implementation remain unclear and will require regulatory guidance before the 2027 implementation date.

The exact definition and scope of Sensitive Health Information needs clarification. Which specific categories of health information will receive the more restrictive access controls? Will there be a published list, or will determinations be made case-by-case? How will healthcare providers classify information as sensitive or not? These details will significantly impact how organizations implement the two-tier access model.

Detailed technical standards for NEHR integration, data formatting, encryption requirements, and transmission protocols need publication. Healthcare organizations cannot complete system integration without clear technical specifications. The recent release of SS719:2025 and SS720:2025 standards represents progress, but additional detailed specifications will be needed to enable consistent implementation across thousands of diverse healthcare providers.

The process for applying for derived information access requires clarification. What information must applicants provide? How long does the approval process take? What criteria guide the Minister’s determination of whether an application relates to or promotes public health? Are there published guidelines or precedents? Will approval decisions be made public? Researchers and public health organizations need clarity on these processes to plan projects.

The enforcement approach the Ministry of Health will take is unclear. Will there be a grace period during initial implementation for good-faith compliance efforts, or will strict liability apply from day one? How will the Ministry prioritize enforcement actions? What circumstances might warrant criminal penalties versus administrative sanctions? How will the Ministry balance encouraging rapid compliance with penalizing serious violations? These questions affect how organizations approach compliance and assess their risk exposure.

The role of patient advocacy in oversight is undefined. Will patient advocacy organizations have formal opportunities to provide input on implementation? Will there be independent privacy oversight mechanisms beyond the Ministry of Health? How will patient complaints about inappropriate access or privacy violations be handled? Patient trust in the system depends partly on assurance that there are accountability mechanisms beyond self-regulation by the healthcare sector.

International reciprocity and medical tourism implications need consideration. How will Singapore’s approach interact with other countries’ health information sharing frameworks? Will foreign healthcare providers treating Singapore residents be required to contribute to NEHR? How will information sharing work for Singaporeans receiving care abroad? These questions matter for Singapore’s significant medical tourism sector and for Singaporeans who receive care internationally.

What This Means for Privacy Practice

The Health Information Bill represents a significant development in privacy law that extends beyond Singapore’s healthcare sector. For privacy practitioners globally, it offers a case study in what happens when a jurisdiction decides that collective benefits—in this case, healthcare quality and coordination—outweigh traditional individual privacy preferences about data sharing.

The legislation demonstrates that consent-based frameworks, while prevalent in modern data protection law, are not inevitable or universal. When policymakers determine that mandatory data sharing serves sufficiently important public purposes, they can and do override individual choice. This is particularly likely in sectors like healthcare where incomplete participation can undermine the system’s core functionality.

For lawyers advising clients in Singapore’s healthcare ecosystem, the immediate priority is navigating the complex interplay between Health Information Bill requirements, Personal Data Protection Act obligations, and practical operational realities. The 2027 implementation timeline demands urgent action on multiple fronts: technical integration, cybersecurity enhancement, policy revision, staff training, and patient communication.

The dual compliance framework created by layering HIB on top of PDPA is particularly challenging. Organizations cannot simply update their practices for one law and assume they’ve achieved compliance. They must map out how both frameworks apply to specific data processing activities, identify where obligations overlap and where they diverge, and ensure their practices satisfy both simultaneously. This requires familiarity with both legal frameworks and careful attention to how they interact in specific contexts.

The aggressive two-hour breach notification requirement demands particular attention. Organizations that have not previously needed to maintain 24/7 incident response capabilities will need to develop them. The timeline is tight enough that it effectively requires continuous monitoring and immediate escalation protocols. Traditional business-hours-only approaches to breach response will not suffice.

Vendor management takes on new importance given that healthcare organizations bear responsibility for vendor compliance despite the Health Information Bill not directly imposing obligations on vendors. Organizations need to carefully review their vendor relationships, strengthen contractual language around security and compliance obligations, implement more rigorous vendor due diligence processes, and potentially reconsider vendor selection decisions if current vendors cannot meet HIB requirements.

For organizations with cross-border operations, data localization and processing questions require careful analysis. While Singapore does not have blanket data localization requirements, the mandatory contribution to a domestically-hosted NEHR system creates practical pressure toward local processing of Singapore patient data. Multinational healthcare organizations need to evaluate whether their global processing models can accommodate Singapore-specific data flows or whether separate infrastructure is required.

Looking ahead, the success or failure of Singapore’s mandatory approach may influence other jurisdictions grappling with similar healthcare coordination challenges. Privacy lawyers should monitor Singapore’s implementation to understand both the benefits of comprehensive health data sharing and the privacy implications of mandatory participation systems. The balance Singapore strikes between healthcare innovation and privacy protection will provide valuable lessons for policymakers and practitioners globally.

The Health Information Bill ultimately exemplifies a fundamental tension in modern privacy law: the conflict between individual autonomy over personal information and collective benefits that may require comprehensive data sharing. Singapore has chosen to prioritize the collective benefit, at least in the healthcare context. Whether this approach succeeds in delivering better healthcare outcomes without unacceptable privacy costs remains to be seen. Privacy lawyers must remain vigilant in protecting individual rights while facilitating legitimate data uses, ensuring that the promise of better coordinated care does not come at an unacceptable privacy cost.