We are always working hard to unlock safe data insights and thanks to a recent Ontario guideline book we are able to put together an in depth guideline showcasing the foundations de-identification.

The IPC says “As the demand for data increases, data custodians require effective processes and techniques for removing personal information from the data so it can be used to draw important insights and improve services without compromising privacy or public trust. An important tool in this regard is de-identification.” This captures the core tension of 2025–2026 data governance explosive growth in secondary data uses (e.g., ML training, population health analytics, policy evaluation) versus rising privacy expectations amid high-profile breaches and AI ethics debates.

De-identification is defined as “the general term for the process of removing personal information from a record or dataset.” When done effectively, the result “no longer contain[s] personal information,” exempting it from many consent, access, correction, and breach rules under Ontario law. Yet the IPC is clear-eyed: risk is never zero. The goal is very low re-identification risk—”removal of information that identifies an individual or could be used, either alone or with other information, to identify an individual based on what is reasonably foreseeable in the circumstances.” This “reasonably foreseeable” phrasing echoes statutory definitions of personal information (PI/PHI) and Canadian jurisprudence.

The section stresses complexity: de-identification is “complex and technically challenging.” It positions the guidelines as a “solid base” for beginners, not a replacement for expertise. Custodians are urged to seek privacy, legal, and technical advice. Automation is encouraged—software tools can handle parts of the process (e.g., variable classification, risk modeling, transformations like generalization or noise addition)—but the IPC remains vendor-neutral, advising due diligence.

The centerpiece is the Structured Data De-Identification Checklist (presented as a clipboard-style infographic with checkmarks). This ~18-item list provides an operational roadmap, assuming a single release but adaptable for ongoing ones:

– Grasp terminology and define disclosure types (e.g., identity disclosure).

– Secure expertise and clarify objectives/purposes.

– Notify affected individuals about de-identification and its goals.

– Choose a release model (public/open, non-public internal, non-public external/third-party).

– Identify recipients and classify variables (direct vs. indirect identifiers).

– Set a re-identification risk threshold (typically “very low”).

– For non-public sharing: define controls, draft data sharing agreements (DSAs), ensure compliance.

– Perform pseudonymization + indirect identifier transformations.

– Measure post-transformation risk (confirm below threshold).

– Document everything.

– Monitor the environment for changes (e.g., new public datasets that could enable linkage).

– Handle re-identification claims.

– Establish governance for de-identified data (e.g., training teams, managing overlapping releases).

This checklist is one of the document’s most actionable contributions, distilling the entire process into verifiable steps. It promotes proactive governance—e.g., notice to individuals (even if consent isn’t required) and ongoing monitoring—to prevent risks from re-emerging.

The introduction also nods to broader context: Ontario laws permit de-identified data for secondary purposes without consent in many cases (e.g., PHIPA s. 37 for planning/research). Globally, it aligns with pseudonymization under GDPR Art. 4(5) and anonymization concepts elsewhere, while staying Ontario-specific. Abbreviations (e.g., PHIPA, GDPR, SDG for synthetic data generation) prepare readers for later sections.

Overall, Section 1 frames de-identification as an essential, balanced tool—not a silver bullet, but a rigorous, risk-managed practice that enables data-driven progress while safeguarding individuals. It demystifies the topic, sets realistic expectations, promotes tools and expertise, and equips custodians with a clear starting checklist. In doing so, it builds confidence that privacy and utility can coexist responsibly. As we provide guidance below download directly the de-identification guide for privacy, transparency, and empowerment from the IPC here.

Clarifying the Language of Privacy Protection: Core Terms and Distinctions in De-Identification

The process of safely removing identifying details from structured datasets begins with shared understanding. Words that describe privacy techniques vary widely depending on industry, academic field, or country. Health organizations might emphasize one set of phrases, financial institutions another, while computer scientists, statisticians, and regulators each bring their own nuances. Without clear agreement on definitions, discussions about protecting data can quickly become confusing or lead to mismatched expectations.

This section focuses on building that common language, particularly around two central ideas often confused: pseudonymization and full de-identification. It also introduces related concepts that shape how risk is evaluated and managed.

Pseudonymization involves replacing or obscuring direct identifiers—elements that immediately point to a specific person, such as full names, exact home addresses, social insurance numbers, telephone numbers, email addresses, or unique account identifiers. Common techniques include removal (simply deleting the field), encryption (scrambling values so they can be reversed with a key), hashing (one-way mathematical transformation), tokenization (substituting values with meaningless placeholders from a lookup table), or randomization (replacing with unrelated codes). After pseudonymization, no obvious direct identifiers remain in the dataset.

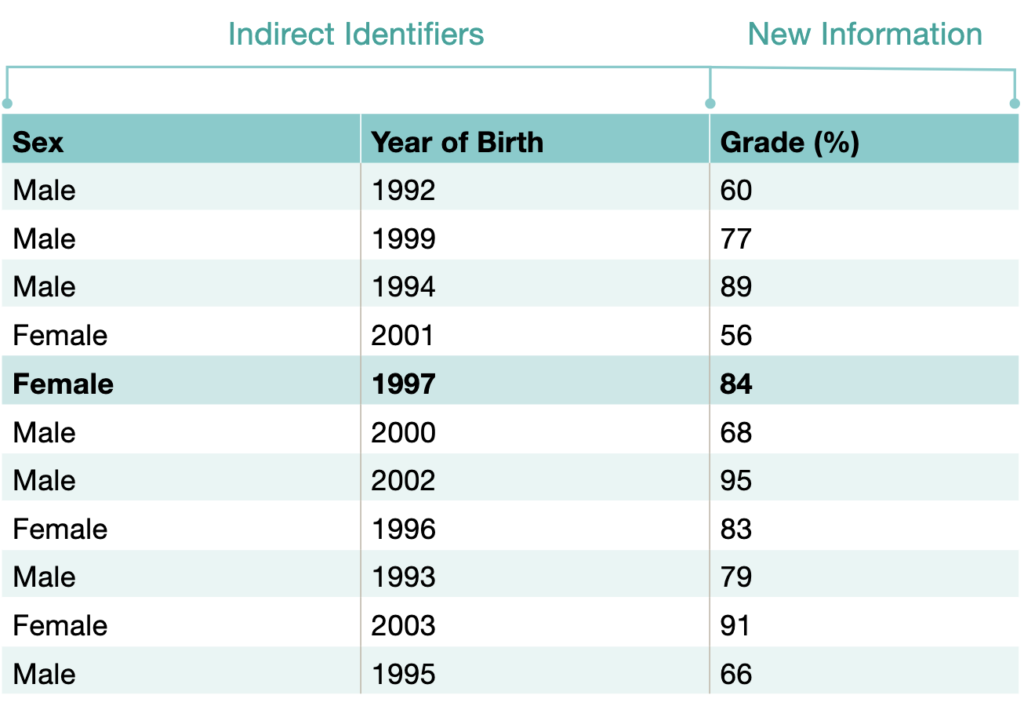

While this step offers meaningful privacy benefits—making casual inspection or simple misuse harder—it rarely eliminates all personal information. In most real-world scenarios, the remaining data still allows reasonable re-identification when combined with other sources. For example, a dataset with only birth year, postal code, and rare medical diagnosis codes can still single out individuals even after names are replaced with random strings. Pseudonymized records are therefore generally still treated as personal information under privacy laws, carrying the same obligations for consent, access requests, correction rights, and breach reporting.

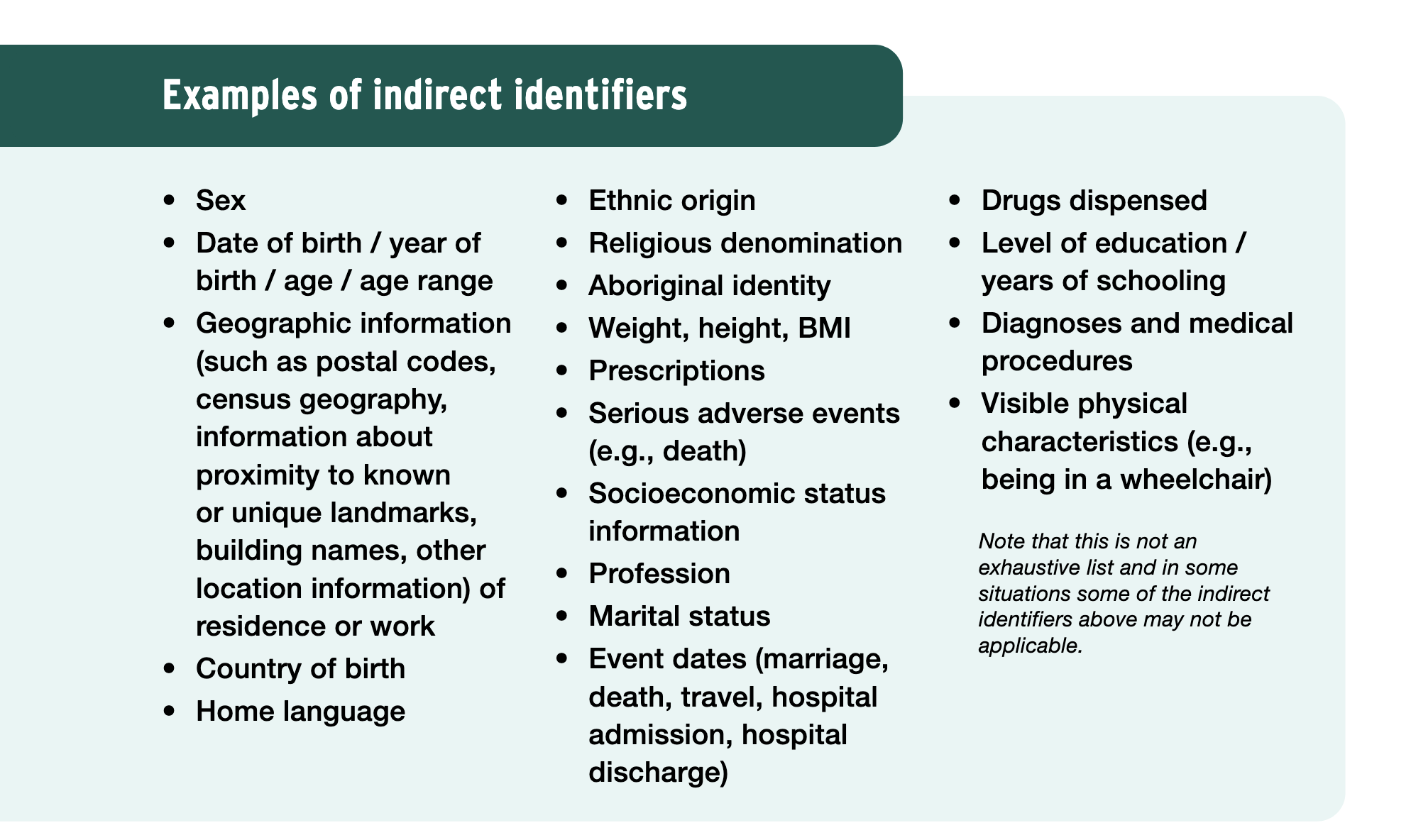

De-identification goes further. It starts with pseudonymization as a prerequisite, then applies additional transformations to the indirect identifiers that linger. Indirect identifiers are attributes that do not name someone outright but can contribute to identification when combined: age or birth year, gender, postal code or neighborhood, occupation, hospital admission dates, diagnosis codes, visit frequencies, lab result ranges, or even seemingly innocuous details like employment start month or course enrollment term. The goal is to alter these fields so that, taken together, they no longer point uniquely (or near-uniquely) to any real person in a foreseeable way.

Transformations for indirect identifiers include:

– Suppression: removing the field entirely when it poses too much risk.

– Generalization: reducing precision, such as changing exact birth dates to birth year, or full postal codes to the first three characters (forward sortation area).

– Categorization: grouping values into broader buckets, like age ranges (18–29 instead of 24) or income bands.

– Random noise addition: perturbing numeric or date values slightly (e.g., adding or subtracting a random number of days to admission dates).

– Sampling or subsetting: releasing only a portion of records to reduce uniqueness.

– Advanced synthetic approaches: training machine learning models on the original patterns and generating entirely new, artificial records that mimic statistical properties without copying real individuals.

Once these steps are complete and the resulting risk has been measured and confirmed as very low, the dataset is no longer considered personal information. It can be shared, published, or reused without triggering many of the usual privacy protections, provided the transformations hold up under reasonable attack scenarios.

The distinction matters because pseudonymization alone is often insufficient for high-risk releases (such as open data portals), while full de-identification enables broader, safer secondary uses—population health studies, policy evaluation, machine learning development, service planning—without ongoing consent requirements.

Several related terms appear frequently and deserve clarity:

– Personal information (or personal health information): anything that relates to an identifiable individual, alone or combined with other data.

– Direct identifiers: fields that explicitly name or locate someone.

– Indirect (or quasi-) identifiers: the combinatory clues that remain after direct identifiers are handled.

– Re-identification risk: the probability that someone could link a record back to a real person using available background knowledge, motivated attackers, or publicly accessible data.

– Very low risk: the practical target, meaning re-identification is not reasonably foreseeable under the circumstances.

– Disclosure types: primarily identity disclosure (who is who), but sometimes membership disclosure (whether someone is in the dataset) or attribute disclosure (learning sensitive traits about someone known to be present).

The section emphasizes that terminology must be explicitly agreed upon before any project begins. Misalignment—treating pseudonymized data as fully de-identified, for instance—can lead to inappropriate sharing, regulatory exposure, or eroded public confidence.

Practical implications flow directly from these definitions. Organizations deciding whether to release student performance summaries, hospital utilization statistics, or employee wellness program aggregates need to ask: Are we only pseudonymizing, or are we truly de-identifying? The answer determines permissible release models (open publication vs. controlled access), required safeguards (contracts, audits, separations), and documentation expectations.

In environments where data flows across departments, partners, or sectors, consistent use of these terms prevents costly rework. A health agency sharing pseudonymized claims data with a university researcher might later discover the recipient can re-link records via external registries—highlighting why the full de-identification process, including indirect identifier handling and risk measurement, is essential for higher-risk contexts.

Advanced techniques like synthetic data generation receive brief mention here as one way to transform pseudonymized data, hinting at later appendices. The core message remains: start with clear definitions, recognize pseudonymization as a necessary but usually insufficient first step, and treat de-identification as the rigorous, multi-layered process that achieves very low risk.

By establishing this shared vocabulary early, data custodians, analysts, legal teams, and recipients can align on expectations, select appropriate methods, and document decisions transparently. The result is safer data use that respects privacy while enabling legitimate insights.

Understanding the Spectrum of Risk: Principles and Practical Foundations of De-Identification

Once the basic language is settled—distinguishing pseudonymization from full de-identification—the next layer involves grasping how identifiability actually works in real datasets and why a principled, risk-focused approach matters more than rigid checklists alone. This part shifts from definitions to the underlying principles that guide every decision in the process. It explains why some data feels obviously sensitive while other data seems harmless until combined in unexpected ways, and it lays out the conceptual framework for balancing privacy protection with meaningful data usefulness.

At the heart of the approach is the idea of an identifiability spectrum. No dataset is simply “identified” or “anonymous.” Instead, records exist along a continuum ranging from directly named individuals at one extreme to completely non-identifiable synthetic patterns at the other. Most real-world structured data falls somewhere in the middle after initial cleaning. The spectrum concept helps decision-makers visualize that de-identification is not a binary switch but a series of deliberate steps that move data progressively toward the low-risk end.

Moving along this spectrum requires understanding the privacy-utility trade-off. Stronger privacy protections—such as removing more fields, applying coarser generalizations, or injecting greater noise—almost always reduce the analytical value of the data. Detailed age might reveal important trends in health outcomes, but grouping everyone into decade-long bands hides those nuances. Exact visit dates enable time-series analysis of service demand, but randomizing them by weeks or months obscures temporal patterns. The challenge is to find the sweet spot where risk becomes acceptably low without rendering the dataset useless for its intended purpose. This trade-off is not abstract; it plays out in every transformation choice and must be explicitly weighed.

All transformations must target both direct and indirect identifiers. Direct identifiers are the obvious ones that get handled first through pseudonymization. Indirect identifiers are the subtler attributes that remain and often pose the greater long-term threat because they are ubiquitous and linkable to external sources. Examples include birth year, gender, postal code prefix, diagnosis category, procedure codes, employment sector, school attended, course enrollment term, or even purchase categories in retail data. Effective de-identification demands that these quasi-identifiers be assessed and modified together, not in isolation, because their combined uniqueness drives re-identification potential.

Risk assessment must always be relative to the data recipient and the context in which the data will be used. A dataset that is acceptably safe when shared internally with strong access controls and contractual prohibitions may become dangerously exposed if released publicly on an open portal. The same transformations that suffice for a trusted research partner might fall short when the recipient is unknown and motivated to re-identify. Context includes the recipient’s technical capabilities, access to auxiliary data, incentives to attack, and legal obligations. A public health agency sharing with another government department operates under very different assumptions than one publishing open data for journalists, academics, or commercial analysts.

For non-public sharing or reuse, controls and context become especially important. Controls are the technical, contractual, organizational, and procedural safeguards that reduce attack likelihood. These might include secure data enclaves, audit logging, data use agreements that ban re-identification attempts, prohibitions on linking to external datasets, limited retention periods, physical separations between teams, role-based access, and regular compliance audits. Context covers the broader environment: Is the recipient bound by similar privacy laws? Do they have a history of responsible data handling? Are there known public datasets that could facilitate linkage?

When strong controls exist and the recipient has limited motive or capacity to re-identify, the required data transformations can be less aggressive, preserving more utility. In contrast, public releases or sharing with unknown parties demand the highest protective measures because controls are minimal or absent. This principle explains why the same underlying dataset might undergo different levels of generalization depending on the release model.

The document illustrates these ideas with clear visual metaphors. One shows a gradient bar moving from fully identifiable (names and addresses present) through pseudonymized (names replaced but other details intact) to de-identified (indirect identifiers coarsened or suppressed) and finally to synthetic (artificially generated records with no direct lineage to real people). Another depicts the trade-off as a seesaw: privacy rising on one side forces utility down on the other, with the goal of keeping both at acceptable levels.

These principles inform every subsequent step. They remind analysts that de-identification is context-dependent, not a one-size-fits-all formula. They underscore that risk is dynamic—new public data releases, advances in linkage techniques, or changes in recipient behavior can shift the spectrum over time. And they highlight the need for ongoing governance to monitor those changes.

In practice, these concepts guide organizations through tough choices. A hospital considering whether to share aggregated emergency department statistics with a municipal planning team must ask: How much detail can we retain while keeping risk very low given the controls in place? A school board releasing performance metrics for program evaluation must weigh whether broad grade bands hide important equity trends or whether finer categories create unacceptable uniqueness in small subpopulations.

By internalizing these principles, data custodians move beyond mechanical application of rules toward reasoned, defensible decisions. They can explain to stakeholders why certain fields were suppressed while others were retained, why one release model required heavier transformations than another, and how the chosen approach respects both individual privacy and the societal value of data-driven insights.

The result is more than compliance—it is a mature privacy practice that adapts to real-world complexity while enabling responsible innovation.

Assessing and Managing Re-Identification Risk: From Basic Models to Practical Thresholds

With the foundational concepts and principles established, attention turns to the core technical challenge: how to actually measure and control the chance that someone could re-identify individuals from a supposedly protected dataset. This section introduces the notion of re-identification risk in concrete terms, explains why it cannot be eliminated entirely, and outlines the modeling approaches that form the backbone of responsible de-identification.

Re-identification risk is fundamentally a probability. It represents the likelihood that an adversary—whether a deliberate attacker, a curious insider, or someone who stumbles across a linkage—can correctly match one or more records in the released dataset to real people using available background knowledge. That knowledge might come from public records, social media, news articles, voter lists, commercial databases, or even casual observation. The risk is never absolute zero because new data sources emerge constantly, linkage techniques improve, and human behavior remains unpredictable. The realistic target is therefore very low risk—low enough that re-identification is not reasonably foreseeable under the specific circumstances of the release.

The guidelines distinguish several types of disclosure that contribute to overall risk. The primary concern is identity disclosure: correctly assigning a real person to a specific record in the dataset. This is the most direct privacy harm and the one most emphasized in Ontario privacy law interpretations. Other types include membership disclosure (learning whether a particular person is present in the dataset at all) and attribute disclosure (inferring sensitive traits about someone known or strongly suspected to be in the dataset). While all matter, the document focuses mainly on identity disclosure because it underpins most regulatory and ethical concerns around personal information.

Risk models vary depending on the type of attack and the context. For deliberate attacks—where a motivated adversary actively tries to re-identify—the probability depends on the adversary’s capacity, resources, and access to auxiliary information. Inadvertent attacks occur when someone unintentionally recognizes a record (for example, recognizing their own or a family member’s data in a small published table). Data breach scenarios assume an unauthorized party obtains the dataset and then attempts linkage. Each scenario requires a tailored probability estimate, and the overall risk is typically a weighted combination of these possibilities.

A key insight is that risk is highly sensitive to uniqueness. If a combination of attributes appears only once (or very rarely) in the released data, even modest background knowledge can lead to identification. Uniqueness is measured at the level of the relevant population, not just the sample being released. A record that looks unique in a small extract might be common in the full population of millions, lowering real risk. Conversely, a seemingly common pattern in a large release can become unique if the release covers a small geographic area or a rare subgroup.

The document illustrates this with practical examples. Consider a dataset of student course performance over three terms. If counts are shown for small classes with detailed demographics (age category, gender, exact grades), a single outlier performance might allow someone familiar with the class to deduce exactly who earned that score. Removing or coarsening those demographics increases group sizes and reduces uniqueness. Another example involves health records where diagnosis, age category, and sex are retained. If one combination is rare, anyone knowing those details about a specific person (perhaps from social conversation) can confidently assign the diagnosis to that individual. Removing one person from the dataset can dramatically change risk for the remaining records, demonstrating how fragile uniqueness can be.

To quantify risk, the approach relies on model-based assessment rather than purely empirical testing (though empirical checks have a role). Model-based methods estimate vulnerability by calculating how many records are unique or near-unique under realistic assumptions about adversary knowledge. For public releases, the model assumes broad auxiliary data availability and high linkage potential. For controlled sharing, it factors in the strength of contractual, technical, and organizational controls that limit what the recipient can do or access.

Thresholds are central to decision-making. The acceptable re-identification risk threshold is not a universal number but a context-specific value, often informed by an invasion-of-privacy assessment. This assessment weighs the sensitivity of the data, the potential harm of identification, the public interest in the data use, and societal norms. Very low risk typically means probabilities in the range of fractions of a percent or lower, depending on the scenario. The threshold must be set explicitly before transformations begin so that analysts have a clear target.

Once the threshold is defined, the process becomes iterative: classify variables, pseudonymize direct identifiers, assess baseline vulnerability from indirect identifiers, apply transformations to increase group sizes or reduce distinguishability, re-measure risk, and continue until the estimated probability falls below the threshold. If utility drops too far before the threshold is met, the release model might need adjustment (e.g., moving from public to controlled access) or the purpose might need re-evaluation.

These risk concepts directly influence release strategy. Public open data requires the most conservative transformations because controls are weakest and adversaries are unconstrained. Custodian-controlled access to a trusted third party allows somewhat less aggressive changes if robust data sharing agreements, audit trails, and prohibitions on linkage are in place. Internal reuse within an organization benefits from the strongest separations and oversight, permitting the highest utility retention.

The emphasis on modeling over blind application of rules reflects lessons from real-world re-identification demonstrations. High-profile cases have shown that simple rules (e.g., removing names and addresses) are insufficient when indirect identifiers remain distinctive. By quantifying risk explicitly, organizations can defend their choices, document that risk is very low, and adapt as new threats emerge.

This risk-centered mindset shifts de-identification from a compliance exercise to a reasoned engineering process. It enables proportionate protection—strong where needed, lighter where context permits while preserving as much analytical value as possible. The result is data that can be used confidently for planning, research, and innovation without exposing individuals to foreseeable privacy harms.

Building the Practical Foundation: Preparing for and Executing De-Identification in Real-World Scenarios

With the conceptual groundwork laid—clear terminology, the identifiability spectrum, the privacy-utility balance, and the centrality of measured risk—the focus shifts to actionable execution. This stage translates principles into a structured, repeatable process that data custodians can follow when handling structured datasets. The emphasis is on preparation, decision points, iterative risk reduction, and documentation, ensuring that de-identification is defensible, transparent, and adaptable over time.

The process begins long before any data is touched. Preparation involves assembling the right team, clarifying objectives, and making upfront choices that shape everything that follows. Expertise is non-negotiable. Effective de-identification requires a blend of skills: privacy and legal knowledge to interpret obligations and thresholds, statistical or computational proficiency to model risk and apply transformations, and domain understanding to preserve meaningful utility. Small organizations might rely on a single analyst with broad training, while larger ones form multidisciplinary teams or engage external specialists. The key is confirming that the necessary competencies are in place before proceeding.

Objectives must be explicit. Why is the data being de-identified? Is it for internal analytics, public open data publication, research sharing with a university, or controlled access by a policy partner? The purpose directly influences the acceptable risk level, the required controls, and how much utility can be retained. A project aimed at broad public insights might prioritize maximum openness and therefore demand stronger anonymization, while internal reuse for service planning might allow finer detail under tight governance.

Notice to individuals is another early requirement. Even when consent is not legally needed for secondary use of de-identified data, informing people that their information is being processed in this way promotes transparency and trust. Notice can be general (e.g., via privacy notices or website postings) rather than individualized, but it should describe the broad goals and assure that the result will not reasonably identify anyone.

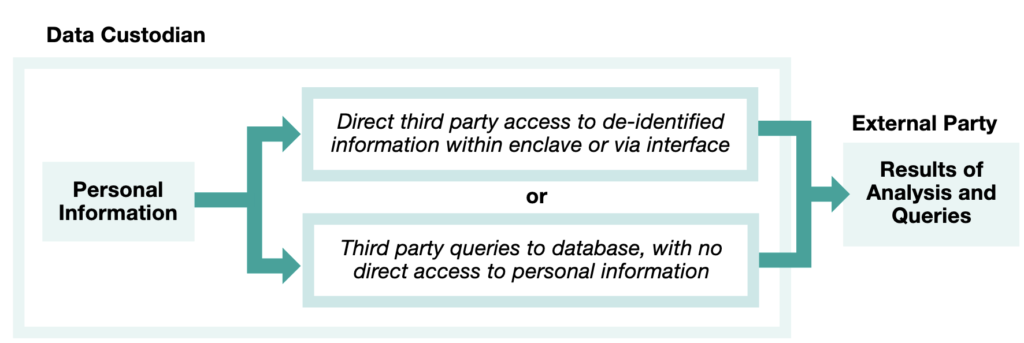

The release model is a pivotal decision. Public release (open data) assumes minimal controls and unknown recipients, requiring the most conservative transformations. Non-public internal sharing benefits from organizational separations, access logs, and policy prohibitions. Non-public external sharing to a specific third party allows tailored controls through contracts and technical restrictions. Custodian-controlled access—where the original holder retains the raw data and provides query results or limited views—further reduces exposure. Choosing the model early prevents mismatched expectations later.

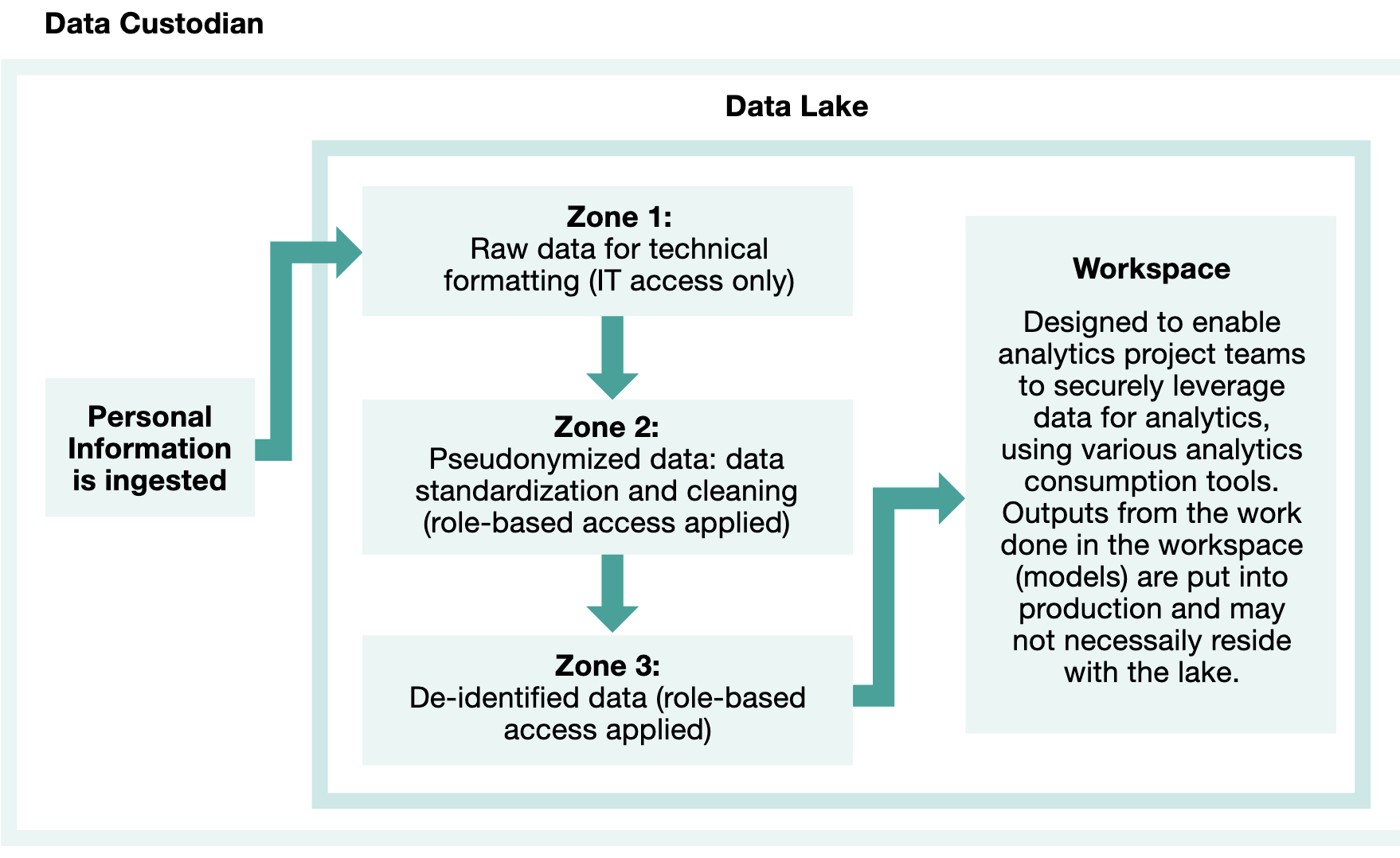

Once the model is set, variables are classified. Direct identifiers (names, exact addresses, health card numbers) are handled first through pseudonymization techniques such as removal, hashing, tokenization, or encryption. Indirect identifiers (age ranges, postal code prefixes, diagnosis groups, dates of service) receive closer scrutiny because they drive residual risk. Classification is not always obvious—fields like “admission month” or “course enrollment term” can become quasi-identifiers in small populations—so systematic review is essential.

Risk threshold setting follows. The threshold defines “very low” in concrete terms for the specific context. It draws from an invasion-of-privacy assessment that considers data sensitivity, potential harm from identification, public interest in the use, and societal norms. Thresholds are often expressed as maximum acceptable probabilities (e.g., below 0.1% for public releases) or minimum group sizes (e.g., no combination appearing fewer than five times in the relevant population). Setting it explicitly creates a measurable target.

With preparation complete, execution begins. Pseudonymization clears direct identifiers. Then risk is measured in the pseudonymized dataset to establish baseline vulnerability. For public releases, this often assumes broad auxiliary data availability and calculates uniqueness against a defined population (e.g., all residents of a province or city). For controlled sharing, the assessment factors in the recipient’s limited access and contractual bans on linkage.

If baseline risk exceeds the threshold, transformations are applied to indirect identifiers. Common methods include suppression (removing risky fields), generalization (coarsening values to increase group sizes), categorization, random perturbation, or subsampling. Each change is re-evaluated—risk is recalculated until it falls below the threshold or utility becomes unacceptable. When utility suffers too much, options include switching release models, narrowing scope, or abandoning the release.

Controls are layered in for non-public scenarios. Data sharing agreements spell out prohibitions on re-identification attempts, linkage to external sources, redisclosure, and retention limits. Technical separations (e.g., different environments for raw and de-identified data), audit trails, and compliance monitoring reinforce protection. Checking that these controls are actually implemented—through walkthroughs, testing, or third-party review—ensures they are not merely theoretical.

The final risk calculation combines data vulnerability (from the transformed dataset) with attack probabilities (deliberate, inadvertent, or breach-related), adjusted for controls. The result must demonstrably meet the threshold. If it does, the process moves to documentation: recording every decision, transformation, risk measurement, and rationale. Clear records support accountability, audits, and future re-assessments if circumstances change.

Ongoing monitoring is built in from the start. New public datasets, advances in re-identification techniques, or shifts in recipient behavior can increase risk over time. A process for periodic review—perhaps annually or after major environmental changes—helps catch emerging issues. Similarly, a mechanism to handle re-identification claims (whether from individuals, media, or researchers) ensures prompt investigation and response.

Internal governance ties everything together. Policies for managing overlapping releases (where one de-identified dataset might interact with another), continuous team training, and version control of de-identification plans prevent drift. Governance also addresses synthetic data generation when traditional methods fall short—training generative models to produce artificial records that preserve patterns without copying real individuals.

This end-to-end process is iterative and evidence-based. It avoids one-size-fits-all rules in favor of context-aware decisions backed by measurement. A hospital sharing emergency visit patterns with a municipal planner might retain detailed age bands and diagnosis groups under a strong data sharing agreement, while the same data released publicly would require heavy generalization. A school board publishing performance aggregates might suppress small class details entirely for openness.

By following this structured path, organizations achieve more than compliance—they build defensible, proportionate protection that enables data to serve public good while respecting individual privacy. The result is sustainable data use that can evolve with changing needs and threats.

Navigating Release Models and Controls: Choosing the Right Path for Safe Data Sharing

The way de-identified data is shared or accessed dramatically shapes the level of protection needed and the amount of analytical detail that can realistically be preserved. Different release models carry different assumptions about who might see the data, what they might do with it, and how tightly the environment can be controlled. Understanding these distinctions helps organizations select an approach that matches the purpose, minimizes unnecessary privacy loss, and maximizes legitimate insight generation.

Public release—often called open data—represents the highest exposure scenario. Once published on a portal, website, or repository, the dataset becomes accessible to anyone worldwide without registration, contracts, or oversight. Recipients are completely unknown, their motives unpredictable, and their access to auxiliary data (public records, social networks, commercial databases) potentially vast. In this context, transformations must be the most conservative: heavy generalization, suppression of risky fields, or even synthetic generation to ensure that re-identification remains very low even under worst-case assumptions. The trade-off is clear—utility is often reduced because broad openness demands broad protection. Examples include municipal open data portals publishing aggregated health statistics, school performance summaries, or transportation usage patterns for public benefit and transparency.

Controlled non-public sharing offers more flexibility. When data moves only within an organization or among trusted related entities (such as hospitals within the same health network or government departments under common privacy obligations), internal separations and policies provide meaningful safeguards. These might include physical or logical separation of teams handling raw versus de-identified data, strict role-based access, audit logging, and prohibitions on linkage or redisclosure. With these controls in place, indirect identifiers can often retain more precision—narrower age bands, finer geographic detail, or exact dates—because the risk of deliberate or inadvertent attack is constrained by organizational accountability and oversight. The result is higher utility for internal planning, quality improvement, or cross-departmental analytics while still achieving very low risk.

Sharing with an external third party under a formal agreement sits between these extremes. Here, the recipient is known and identifiable, allowing tailored controls through a data sharing agreement (DSA). The DSA typically prohibits re-identification attempts, bans linkage to external sources, limits retention periods, requires secure storage and transmission, and mandates destruction or return of data when the purpose ends. Technical measures—encrypted transfers, access restricted to named individuals, regular compliance reporting—further reduce exposure. Because these controls meaningfully lower attack probability, the dataset can often keep more granular attributes than a public release would allow. This model suits research collaborations, policy evaluations, or service partnerships where a specific organization needs detailed but protected data to fulfill a defined objective.

Custodian-controlled access takes protection further still. Instead of handing over a full dataset, the original holder retains possession and provides only limited, query-based views or aggregated results. The recipient never sees the raw (even pseudonymized) records; they submit questions and receive summarized outputs. This architecture drastically reduces linkage risk because no complete copy exists outside the custodian’s secure environment. It is particularly valuable for highly sensitive data or when the recipient’s technical capacity or motives are uncertain. Examples include secure research portals where analysts run statistical queries without downloading underlying tables, or dashboards that display trends without exposing individual-level records.

These models are not rigid categories but points along a continuum of control strength. Stronger controls permit lighter transformations, preserving utility. Weaker or absent controls demand heavier ones. The choice depends on the purpose, the sensitivity of the information, the potential harm of identification, and the public interest served by the data use. A public health agency might choose open release for broad awareness of disease trends but shift to custodian-controlled access when sharing detailed case-level data with a specialized research institute. A school board might publish coarse performance aggregates openly while sharing finer demographic breakdowns internally or with a trusted evaluation partner under agreement.

Visual representations help clarify these differences. One common illustration shows a funnel: broad public release at the wide top requires the strongest anonymization to filter out risk; as controls tighten toward the narrow bottom (custodian-controlled or internal reuse), more detail survives. Another depicts layered barriers—technical, contractual, organizational—surrounding the data, with each layer reducing the effective attack surface and allowing progressively less aggressive data modification.

In all cases, the guiding principle remains proportionality. Protection should be commensurate with risk, not uniformly maximal. Over-protecting safe internal uses wastes analytical potential; under-protecting public releases invites foreseeable harm. By matching the release model to the context and documenting the rationale, organizations achieve balanced outcomes that respect privacy while enabling data to inform decisions, improve services, and advance knowledge.

This decision also influences downstream steps. Public models trigger population-wide vulnerability assessments and strict group-size rules. Controlled models incorporate control strength into probability estimates, often allowing smaller groups or finer categories. The release choice is therefore not an afterthought but a foundational element that shapes the entire de-identification strategy.

Ultimately, thoughtful selection of release model and controls turns de-identification from a blunt instrument into a precise tool. It allows data to flow where it is needed—internally for efficiency, externally for collaboration, publicly for transparency—while keeping re-identification risk demonstrably very low in every scenario.

Advanced Risk Measurement in Practice: Modeling Vulnerability, Population Context, and Attack Scenarios

The measurement of re-identification risk moves beyond broad concepts into precise, repeatable techniques that account for real-world data characteristics and adversary behavior. This stage focuses on how to quantify vulnerability in structured datasets, why population-level uniqueness matters more than sample-level observations, and how different attack types require distinct probability models. These tools allow custodians to demonstrate objectively that risk has been reduced to very low levels before any sharing or release occurs.

Data vulnerability is the starting point for most assessments. It reflects how distinctive or rare a record’s combination of attributes is within the relevant population. A record is considered vulnerable if its indirect identifier pattern appears only a few times (or once) in the population from which the sample was drawn. High vulnerability means even modest background knowledge can lead to correct linkage. Low vulnerability means many people share similar patterns, making confident identification much harder.

A common mistake is measuring uniqueness only within the released sample. If a dataset covers a small geographic area or rare subgroup, combinations that look common in the sample might be extremely rare in the full population. Conversely, patterns that appear unique in a large extract could be ordinary when viewed against provincial or national totals. The correct approach always references the population size and distribution, not just the sample. Generalization—broadening categories like age or location—increases group sizes and directly lowers measured vulnerability by making more records indistinguishable from one another.

Two primary attack directions illustrate why population context is critical. In a sample-to-population attack, the adversary starts with a record from the released dataset and tries to find a matching person in external population data. This is the classic re-identification scenario: the released data is the known starting point, and the goal is to link it to a real identity. Risk here depends on how rare the released pattern is in the broader population. If the pattern matches only one or very few people, the attack succeeds with high probability.

The reverse—population-to-sample attack—starts with known information about a real person (from public records or personal knowledge) and checks whether that person appears in the released dataset. This attack targets membership disclosure: does the dataset contain this individual at all? It is particularly relevant when the release covers a small or defined group (a single workplace, school cohort, or hospital ward), because presence itself can reveal sensitive information. Both directions must be considered, though sample-to-population is often the dominant concern for identity disclosure in public or semi-public releases.

To quantify these risks, model-based approaches dominate because exhaustive empirical testing against all possible auxiliary data is impossible. Models estimate vulnerability by calculating group sizes for every unique combination of quasi-identifiers in the dataset, then mapping those sizes back to the population. Average vulnerability provides a summary statistic, while maximum or tail vulnerability highlights the riskiest records. The overall re-identification risk combines this vulnerability with the estimated probability of an attack occurring.

Attack probabilities differ by scenario. Deliberate attacks assume a motivated adversary with resources, access to auxiliary data, and intent to re-identify. The probability depends on the perceived value of success, the effort required, and the strength of controls (if any). Inadvertent attacks involve accidental recognition—someone spots their own record or a family member’s in a table and realizes the connection without trying. These are rarer but harder to prevent entirely. Data breach attacks assume unauthorized access to the de-identified dataset followed by linkage attempts; risk here hinges on breach likelihood and post-breach capabilities.

Equations formalize these relationships. Overall risk is a product or weighted sum of vulnerability and attack probability, adjusted for disclosure type and context. For public releases, models often assume high attack probability due to open access. For controlled environments, strong mitigating controls (contracts, audits, separations) substantially reduce that probability, allowing higher vulnerability to remain acceptable.

Figures and examples make these ideas concrete. One shows how generalization enlarges group sizes: an initial dataset with many unique combinations becomes safer as categories broaden, with vulnerability dropping as more records share the same generalized pattern. Another contrasts sample uniqueness versus population uniqueness, highlighting records that are rare in one view but common in the other. Visuals of matching processes illustrate step-by-step linkage under sample-to-population attacks: taking a released record, searching the population for matches, and assessing how many plausible candidates remain.

Practical application involves defining the population carefully. For provincial health data, the population might be all residents of Ontario. For workplace wellness data, it might be employees in a specific region or industry. The choice affects every calculation—using too small a population overestimates risk, while too large underestimates it. Documentation must justify the population definition and any assumptions about its distribution.

These measurement techniques enable evidence-based decisions. If vulnerability remains too high after initial transformations, further generalization, suppression, or subsampling can be applied until group sizes meet predefined criteria (often a minimum threshold like five or ten equivalent records per pattern). When average risk falls below the target while preserving sufficient utility, the dataset is ready for release under the chosen model.

This rigorous modeling approach addresses past criticisms of de-identification: that simple rules fail against sophisticated linkage. By quantifying both data-inherent vulnerability and external attack likelihood, organizations produce defensible results that can withstand scrutiny from regulators, auditors, or privacy advocates. The process also supports iterative improvement—re-assessing risk if new auxiliary data emerges or if the release scope changes.

In summary, advanced risk measurement turns abstract “very low” goals into concrete, population-aware calculations. It distinguishes between attack types, prioritizes population context over sample artifacts, and integrates controls into probability estimates. When done systematically, it provides the confidence that re-identification is not reasonably foreseeable, enabling safe, high-value data use across diverse contexts.

Synthetic Data and Advanced Techniques: When Traditional Transformations Reach Their Limits

As de-identification practices mature, organizations increasingly encounter situations where conventional methods—suppression, generalization, categorization, or noise addition—cannot simultaneously achieve very low re-identification risk and preserve the statistical properties or analytical value needed for the intended use. In these cases, synthetic data generation emerges as a powerful complement or alternative. This approach shifts from modifying real records to creating entirely artificial ones that mimic the patterns, distributions, and relationships in the original dataset without containing any actual personal information.

The core idea is straightforward yet technically sophisticated. A generative model is trained on the pseudonymized original data to learn its underlying structure: correlations between variables, marginal distributions, joint probabilities, and conditional dependencies. Once trained, the model can produce new, synthetic records that statistically resemble the source but have no direct correspondence to real individuals. Because the output is fabricated rather than transformed, the re-identification risk is fundamentally different—it relies on the model not memorizing or leaking specific real cases, rather than on group sizes or uniqueness in the traditional sense.

Several generative modeling families are commonly used for tabular structured data. Tabular generative adversarial networks (GANs) pit a generator (which produces fake records) against a discriminator (which tries to distinguish real from synthetic), forcing the generator to improve until outputs are indistinguishable in distribution. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) learn a compressed latent representation of the data and sample from it to create new instances. Diffusion models, which have gained traction in recent years, gradually add and then reverse noise to reconstruct realistic samples. Transformer-based models, adapted from language processing, treat tabular rows as sequences and capture long-range dependencies effectively. Each family offers trade-offs in training stability, fidelity to complex relationships, and computational cost.

The process typically follows a clear sequence. First, the original dataset is pseudonymized to remove direct identifiers. Preprocessing normalizes numeric fields, encodes categoricals, and handles missing values. The chosen generative model is then trained on this prepared data, with hyperparameters tuned to balance fidelity and privacy. Differential privacy mechanisms—such as adding calibrated noise during training or clipping gradients—can be incorporated to provide formal guarantees against membership inference or attribute leakage. After training, synthetic records are generated in volume matching or exceeding the original, often with post-processing to enforce domain constraints (e.g., age cannot be negative, diagnosis codes must be valid).

Privacy in synthetic data is assessed differently from traditional de-identification. The risk is no longer primarily about uniqueness of attribute combinations but about whether the model has overfit to specific real records or whether an adversary can infer membership or sensitive attributes from the synthetic output. Membership inference attacks test whether a given real record was used in training by comparing its likelihood under the model to synthetic samples. Attribute inference tries to recover hidden traits. Model inversion attempts to reverse-engineer training examples. Strong synthetic methods, especially those with differential privacy, make these attacks provably difficult.

Utility evaluation is equally critical. Synthetic data must support the same analyses as the original: regression coefficients should be similar, classification performance comparable, clustering structures preserved, and summary statistics (means, variances, correlations) closely matched. Utility tests often include downstream task performance, distributional similarity metrics (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, Jensen-Shannon divergence), or visual comparisons of marginal and joint distributions. When utility gaps appear, model architecture, training duration, or privacy budget can be adjusted.

The approach shines in high-risk scenarios. Public release of highly dimensional or sparse data (rare diseases, detailed transaction logs, small subpopulations) often forces extreme generalization under traditional methods, destroying value. Synthetic generation can retain fine-grained patterns while eliminating real records. Longitudinal data with temporal dependencies benefits from sequence-aware models. When overlapping releases are frequent, synthetic data reduces linkage risk across datasets because no real identifiers persist.

Limitations exist and must be acknowledged. Training requires substantial compute for large datasets or complex models. Poorly tuned models can produce low-fidelity outputs that mislead analyses (e.g., implausible correlations). Differential privacy reduces utility in exchange for stronger guarantees, creating the same trade-off seen in other methods. Interpretability can suffer—analysts may struggle to explain why a synthetic dataset behaves as it does. Regulatory acceptance is still evolving; while synthetic data is increasingly recognized as non-personal information when properly generated, some jurisdictions require case-by-case validation.

In controlled non-public contexts, synthetic data can serve as a safe intermediary. A researcher receives synthetic training data for model development, then validates on real held-out data under secure conditions. Organizations test algorithms or dashboards on synthetic versions before touching sensitive originals. This layered approach minimizes exposure while accelerating development.

Integration with traditional methods is common. Hybrid pipelines pseudonymize and lightly transform real data before feeding it to a generative model, or blend real and synthetic records to boost diversity. Post-generation filtering removes any synthetic records that accidentally match rare real patterns too closely.

Overall, synthetic data generation represents the frontier of structured de-identification. It addresses scenarios where traditional transformations force unacceptable utility loss, offers a pathway to formal privacy guarantees, and supports innovation in data-intensive fields like health research, finance, education, and public policy. When combined with rigorous evaluation of both privacy and utility, it enables organizations to share or reuse data that would otherwise remain locked away, all while keeping re-identification risk demonstrably very low.

Sustaining Responsible De-Identification in Evolving Data Landscapes

After detailing the full lifecycle—from preparation and risk modeling through transformations, controls, and advanced synthetic techniques—the guidelines reach their natural close by reinforcing that de-identification is not a one-time event but an ongoing commitment. This final phase emphasizes documentation, monitoring, governance, and continuous improvement, ensuring that the very low risk achieved at release remains valid as time passes and circumstances change. It also reflects on the broader value of the practice: enabling data to serve public good while upholding individual dignity and trust.

Documentation stands as the cornerstone of accountability. Every decision in the process—why a particular release model was chosen, how the population was defined, which transformations were applied and why, the risk calculations before and after, the selected threshold and its justification—must be recorded clearly and accessibly. Comprehensive records serve multiple purposes: they allow internal review and quality assurance, support audits or regulatory inquiries, facilitate re-assessment if new risks emerge, and provide transparency to stakeholders or affected individuals who may later question the handling of their information. Templates in the appendices guide this effort, covering pseudonymization steps, risk assessments, control implementations, and overall de-identification reports. The goal is not bureaucratic overload but defensible reasoning that demonstrates due diligence and proportionality.

Monitoring the environment addresses the dynamic nature of re-identification risk. New public datasets appear regularly—voter rolls, commercial aggregators, social media profiles, open government data—that could enable linkage not foreseen at the time of release. Advances in linkage algorithms, machine learning for pattern matching, or even crowd-sourced identification efforts can shift probabilities. Changes in the recipient’s context (new partnerships, data breaches elsewhere, altered business priorities) may weaken controls. A structured monitoring process—perhaps annual reviews, automated alerts for relevant public data releases, or periodic vulnerability scans—helps detect these shifts early. When triggers occur, the organization revisits the risk assessment, potentially applying additional transformations, restricting access, or withdrawing the data if risk can no longer be kept very low.

Handling re-identification claims requires a clear, responsive protocol. Claims might come from individuals who believe their information has been exposed, journalists investigating privacy risks, researchers testing attack feasibility, or regulators following up on complaints. The response process begins with verification: examining the claim against the documented risk model, checking whether the asserted linkage is plausible under reasonable assumptions, and assessing whether any actual re-identification has occurred. If a breach of the very low risk threshold is confirmed, remedial steps follow—notification where required, mitigation measures, and updates to processes to prevent recurrence. Even unfounded claims offer learning opportunities, revealing blind spots or emerging threats. The guidelines stress fairness and transparency: acknowledge concerns promptly, explain the safeguards in place, and correct errors when they exist.

Governance for de-identified data extends these practices organization-wide. It includes policies for managing multiple or overlapping releases (ensuring that combined datasets do not inadvertently increase risk), training programs to keep de-identification teams current on methods and threats, version control for risk assessments and transformation plans, and integration with broader privacy programs (PIAs, breach response, access request handling). Strong governance prevents drift—where initial rigorous standards erode over time—and fosters a culture that views privacy as integral to data use rather than an obstacle.

The conclusion circles back to the introduction’s core promise: de-identification bridges the gap between data demand and privacy protection. When executed thoughtfully, it unlocks secondary uses—health system planning, educational equity analysis, urban service optimization, scientific research—without compromising the fundamental right to privacy. It does so by design, not by accident, through measured risk reduction, context-aware controls, and ongoing vigilance.

Looking forward, the field continues to evolve. Synthetic generation and differential privacy are gaining maturity, offering stronger formal guarantees. Cross-jurisdictional alignment grows as regulators worldwide grapple with similar challenges. Public expectations for transparency and accountability rise alongside data’s societal role. Organizations that embed these principles deeply—treating de-identification as a mature capability rather than an occasional task—position themselves to navigate future changes responsibly.

In essence, the guidelines end not with finality but with sustainability. De-identification succeeds when it becomes embedded practice: planned meticulously, executed proportionately, documented thoroughly, monitored diligently, and governed effectively. The result is data that informs without identifying, insights that benefit without harm, and trust that endures amid constant innovation.