Over the past several years, “dark patterns” have moved from the margins of academic discussion into the center of legislative, regulatory, and enforcement debates in U.S. privacy law. Legislators have singled them out in statutory text, regulators have treated them as evidence of unfair or deceptive practices, and enforcement agencies have increasingly cited manipulative interface design as a mechanism through which companies extract personal data that consumers would not otherwise disclose.

At the same time, a recurring counterargument has emerged in both policy discourse and litigation defenses: that motivated consumers can protect themselves. According to this view, dark patterns may be undesirable, but they do not warrant regulatory intervention because attentive users can navigate privacy settings, refuse consent, and exercise their statutory rights if they choose to do so. On this account, consumer harm is the product of apathy or inattention rather than manipulation, and government intervention risks paternalism or overregulation.

This “consumer self-help” assumption plays an outsized role in U.S. privacy enforcement. It underlies arguments that interface manipulation does not cause legally cognizable injury, that consent remains voluntary despite design friction, and that disclosure-based regimes are sufficient to safeguard autonomy. It also surfaces implicitly in standing challenges, causation analyses, and assessments of whether a practice is truly “unfair” under federal or state law.

This article examines whether that assumption is empirically defensible. Drawing on experimental evidence from an interdisciplinary study that directly tests consumer behavior in the presence of common privacy-related dark patterns, it evaluates whether even informed, motivated users can reliably protect their privacy through individual effort alone. The findings are striking: when dark patterns are present, consumer self-help systematically fails, even when participants understand their objective and are instructed to maximize their privacy protections.

The article does not argue for any specific regulatory outcome. Instead, it presents the evidence and considers its implications for how lawmakers, regulators, and courts should evaluate claims that consumer choice and vigilance are adequate substitutes for legal intervention.

Dark Patterns and the Architecture of Choice in U.S. Privacy Law

U.S. privacy law has long relied on a model of individual choice mediated through disclosure and consent. Unlike comprehensive data protection regimes that impose broad substantive limits on data collection and use, U.S. frameworks typically emphasize notice, opt-out rights, and consumer decision-making. Within this structure, the design of interfaces through which choices are presented becomes legally consequential.

Dark patterns exploit that dependence. Although definitions vary, dark patterns are commonly understood as interface designs that manipulate, confuse, obstruct, or pressure users into making choices they would not otherwise make. In the privacy context, this often means inducing consumers to disclose personal information, agree to tracking, or forgo statutory rights through design rather than through explicit misrepresentation.

Recent U.S. privacy statutes explicitly acknowledge this phenomenon. State comprehensive privacy laws increasingly prohibit consent obtained through manipulative or deceptive interfaces, signaling legislative recognition that design can undermine voluntariness even where formal disclosures exist. Regulators have similarly framed dark patterns as a species of unfairness or deception, particularly when interface design subverts reasonable consumer expectations or imposes undue friction on the exercise of rights.

Yet these legal developments coexist uneasily with a persistent reliance on consumer agency. Even as statutes restrict dark patterns, they continue to grant consumers rights that must be exercised through digital interfaces. This creates a tension: if consumers are expected to navigate settings and assert rights, but interface design systematically frustrates those efforts, the effectiveness of the legal regime depends on whether self-help is realistically achievable.

In litigation, this tension often surfaces through arguments that consumers could have avoided harm by reading disclosures more carefully, clicking different options, or persisting through multiple screens. Defendants invoke these possibilities to challenge allegations of coercion, to contest causation, or to argue that any resulting data sharing reflects genuine consumer preference rather than manipulation.

The validity of these arguments turns on an empirical question that has historically gone unanswered: when faced with common dark patterns, can consumers who are motivated and informed actually protect their privacy through individual effort?

The Experimental Framework: Testing Consumer Self-Help Directly

The study at the center of this analysis was designed to answer that question directly. Rather than relying on surveys or self-reported attitudes, the researchers constructed an experimental environment that closely mirrors real-world privacy decision-making. Participants interacted with a simulated video-streaming website that required them to configure privacy settings before accessing content.

Crucially, participants were not passive users. They were explicitly instructed that their objective was to maximize their privacy protections. They were told, in advance, that the study concerned privacy settings and that their task was to configure those settings in a way that minimized data sharing. In other words, the experiment did not test inattentive or indifferent consumers; it tested users who were both informed and motivated.

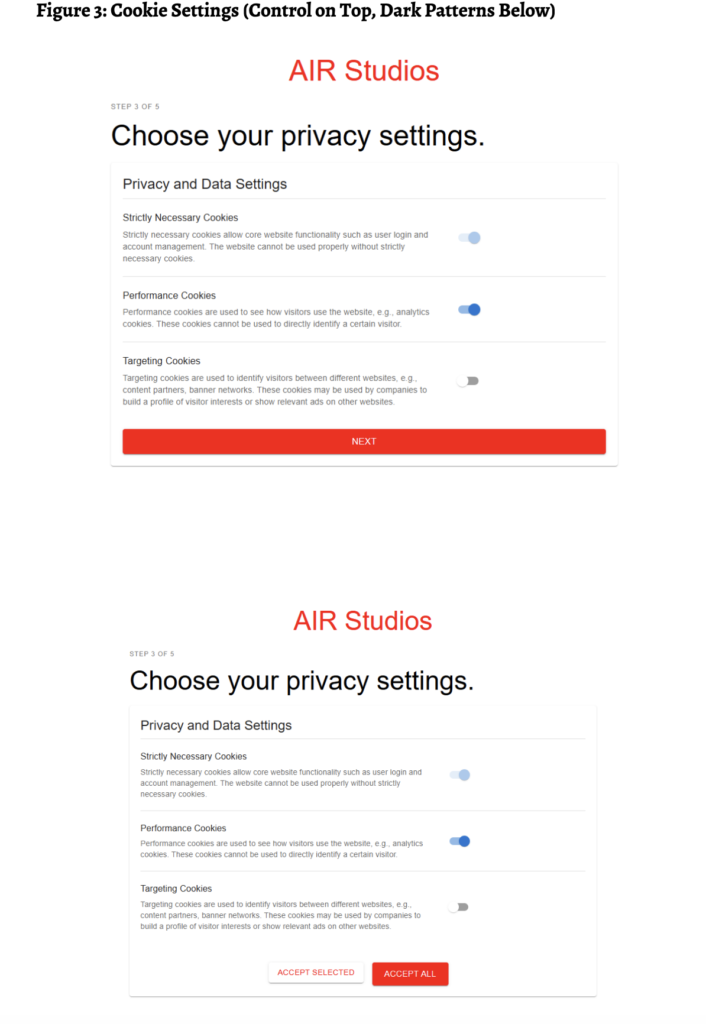

The interface presented to participants varied across experimental conditions. Some users encountered a baseline design without manipulative elements. Others encountered versions of the same privacy settings that incorporated specific dark patterns commonly observed in commercial products. These included obstruction, interface interference, preselection, confusion, and, in a novel contribution, nagging.

By holding the underlying privacy options constant and varying only the interface design, the experiment isolated the causal effect of dark patterns on consumer behavior. This design choice is significant for legal analysis. It allows the results to speak directly to questions of causation and responsibility, rather than conflating manipulation with differences in substantive choices or information availability.

The outcome measured was straightforward: whether participants succeeded in selecting the most privacy-protective options available to them. Because the “correct” outcome was unambiguous and aligned with participants’ stated goals, any deviation from that outcome could be attributed to interface effects rather than preference heterogeneity.

The results challenge the core premise of consumer self-help. Across multiple forms of dark patterns, participants routinely failed to achieve their privacy objectives. Even when users knew what they were supposed to do, interface design materially altered their behavior, leading them to surrender personal information they were attempting to protect.

The sections that follow examine these findings in detail, focusing on how specific dark patterns operate, why they are effective, and what their persistence implies for enforcement, litigation, and the future of U.S. privacy regulation. For the most in depth dark pattern academic paper we suggest reading this 59 page document from the University of Chicago.

Image courtesy of: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5084827

Empirical Findings: Why Consumer Self-Help Breaks Down

The experimental results reveal a consistent pattern: when dark patterns are embedded into privacy interfaces, even informed and motivated consumers struggle to protect their personal information. This failure is not marginal. It is systematic, replicable across multiple interface designs, and robust to participants’ awareness of their own objectives.

Across all tested conditions, participants exposed to dark patterns were significantly less likely to select the most privacy-protective settings than those interacting with a neutral interface. This divergence occurred despite identical underlying choices and despite explicit instructions to maximize privacy. The implication is straightforward but legally consequential: interface design alone can override consumer intent.

Each category of dark pattern operated through a distinct mechanism, yet all shared a common effect. They increased cognitive load, imposed friction asymmetrically, or exploited behavioral heuristics in ways that degraded consumers’ ability to execute deliberate choices. The result was not confusion in the abstract, but measurable surrender of personal data.

Obstruction: Friction as a Tool of Extraction

Obstruction dark patterns function by making privacy-protective choices more difficult to access than privacy-invasive alternatives. In the experimental interface, this took the form of additional clicks, nested menus, or delayed access to relevant settings. The privacy-invasive option, by contrast, was presented as the default or surfaced prominently.

Participants encountering obstructive designs were substantially less likely to reach and activate the most protective settings, even though they knew such settings existed and had been instructed to find them. Many abandoned the effort partway through the configuration process, not because they preferred data sharing, but because the path to privacy required persistence that the interface actively discouraged.

From an enforcement perspective, obstruction is particularly salient because it leaves formal choice intact. Consumers are not barred from opting out; they are merely burdened. Yet the data demonstrates that these burdens are not neutral. They predictably alter outcomes, transforming nominal choice into practical acquiescence.

In litigation, obstruction challenges defenses that frame consent as voluntary simply because an option technically exists. The experiment shows that when exercising that option requires navigating intentionally hostile design, consumer failure is not evidence of preference but of manipulation.

Interface Interference: Diverting Attention at the Moment of Choice

Interface interference operates by distracting users from privacy-protective options at critical decision points. This can include visually emphasizing less protective choices, interrupting decision flows with unrelated prompts, or embedding privacy settings within cluttered or misleading layouts.

In the experiment, interface interference reliably reduced the likelihood that participants selected optimal privacy settings. Even when users understood their objective, visual and structural distractions redirected attention toward default or recommended options that favored data sharing.

This finding is significant for claims that disclosures cure manipulation. The presence of information does not guarantee its effective use. When interfaces are engineered to divert attention away from protective choices, disclosure becomes functionally inert.

For enforcement agencies, interface interference supports the view that manipulation can occur without false statements or omissions. Design itself becomes the deceptive element, shaping behavior by steering attention rather than misrepresenting facts.

Preselection: Defaults as Behavioral Anchors

Preselection dark patterns rely on defaults. Privacy-invasive options are selected in advance, requiring users to affirmatively change settings to achieve greater protection. While defaults are often defended as efficiency-enhancing, the experimental evidence underscores their power to anchor behavior.

Participants exposed to preselected privacy-invasive defaults were markedly less likely to override those settings, even when doing so aligned with their stated goals. The act of changing defaults imposed a psychological and practical cost that many users did not overcome.

This effect persisted despite explicit instructions to maximize privacy. The presence of a default conveyed an implicit recommendation, subtly reframing the decision from an active choice to a deviation from the norm.

In legal contexts, preselection complicates arguments that consumers “agreed” to data sharing through affirmative consent. When consent is the product of inertia induced by defaults, its voluntariness becomes contestable.

Confusion: Ambiguity as a Compliance Strategy

Confusion dark patterns exploit ambiguous language, inconsistent terminology, or complex explanations to obscure the consequences of privacy choices. In the experimental interface, confusion was introduced through unclear labels and descriptions that required interpretation rather than simple selection.

Participants encountering confusing interfaces were less successful in identifying and activating privacy-protective options. Even motivated users misinterpreted settings or misunderstood their effects, leading to unintended disclosures.

Importantly, confusion did not merely slow decision-making; it altered outcomes. The cognitive effort required to resolve ambiguity increased error rates and reduced persistence, particularly when combined with other dark patterns.

From an enforcement standpoint, confusion underscores the limits of disclosure-based compliance. Information that cannot be readily understood does not empower consumers. Instead, it shifts the burden of interpretation onto users while preserving the appearance of transparency.

Nagging: Persistent Pressure as an Independent Dark Pattern

One of the study’s most significant contributions is its identification and empirical isolation of “nagging” as a distinct and potent dark pattern. Unlike obstruction or preselection, nagging operates temporally rather than structurally. It involves repeated prompts that pressure users to accept an undesirable term after an initial refusal.

In the experimental setting, participants who declined privacy-invasive options were repeatedly asked to reconsider. These prompts framed acceptance as necessary, beneficial, or inevitable, while refusal required ongoing resistance.

The results show that nagging alone significantly increased the likelihood that participants ultimately surrendered personal information. Over time, persistence eroded resistance, even among users who initially made privacy-protective choices.

This finding is particularly relevant to legal assessments of consent. Traditional analyses often treat consent as a discrete moment. Nagging demonstrates that consent can be worn down rather than freely given, raising questions about the validity of agreements obtained through repeated pressure.

For litigators, nagging provides a factual basis to challenge claims that initial refusal negates later acceptance. The experiment suggests that acceptance following persistent prompting may reflect fatigue rather than genuine assent.

The Visibility Effect: Why “Do Not Sell or Share” Changes Outcomes

While the experimental findings demonstrate the effectiveness of dark patterns in undermining consumer self-help, the study also identifies a countervailing dynamic with substantial implications for U.S. privacy law: the power of clear, visible rights signals. In particular, the experiment highlights the impact of prominently presenting an option analogous to the “Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information” right established under California law.

When participants were shown a clear, conspicuous opt-out option, a super-majority exercised it. This outcome occurred even in the presence of other dark patterns. The availability of a salient, recognizable privacy control materially altered behavior, enabling many users to overcome interface manipulation that otherwise proved effective.

This result is critical because it reframes the narrative around consumer behavior. The widespread exercise of opt-out rights in this condition undermines claims that consumers are indifferent to privacy or unwilling to assert their rights. Instead, it suggests that consumers respond rationally when rights are made visible and actionable.

Importantly, the study distinguishes between visibility and simplicity. The opt-out mechanism did not eliminate all complexity, nor did it necessarily reduce the number of steps required to exercise the right. What mattered was that the option was clearly labeled, consistently presented, and recognizable as a privacy-protective choice.

For enforcement agencies, this finding supports the view that interface design can either suppress or enable the exercise of statutory rights. When rights are buried, obscured, or diluted through design, consumers predictably fail to exercise them. When rights are surfaced clearly, consumers act.

This distinction has legal consequences. It suggests that consumer failure to opt out in many real-world settings should not be interpreted as evidence of consent or preference. Rather, it may reflect the absence of meaningful opportunity to act.

Reassessing Consent, Voluntariness, and Causation

The experimental evidence presented in this study invites a reassessment of several foundational concepts in U.S. privacy enforcement and litigation, including consent, voluntariness, and causation. Each of these concepts assumes a baseline level of consumer agency that dark patterns systematically erode.

Consent, as traditionally understood, presupposes a choice made freely and with sufficient understanding. The data show that when dark patterns are present, consumer choices diverge sharply from stated objectives. This divergence persists even when users are informed, motivated, and attempting to act in their own interest.

Voluntariness is similarly affected. Interface designs that impose asymmetric friction, exploit defaults, or apply persistent pressure do not merely influence preference; they constrain action. The resulting decisions may be formally voluntary yet substantively coerced.

Causation, a frequent battleground in privacy litigation, is clarified by the experimental design. Because the only variable manipulated was interface structure, the observed changes in behavior can be attributed directly to design choices. This undermines arguments that data surrender reflects independent consumer decision-making.

For litigators, these findings provide a framework for connecting interface design to downstream harms. When personal data is collected or shared as a result of manipulative design, the causal chain is not speculative. It is demonstrable.

Implications for Enforcement Strategy

The findings carry significant implications for how regulators and enforcement agencies approach dark patterns. First, they suggest that prohibitions focused solely on deception may be underinclusive. Many effective dark patterns operate without false statements or misleading disclosures.

Second, the evidence supports treating interface manipulation as a standalone source of unfairness. Practices that predictably undermine consumer autonomy, even in the absence of deception, can produce outcomes inconsistent with reasonable consumer expectations.

Third, the study provides empirical grounding for heightened scrutiny of consent flows, particularly where statutory rights are at issue. When the exercise of rights depends on navigating hostile interfaces, formal compliance may mask substantive noncompliance.

Finally, the visibility effect underscores the importance of affirmative design obligations. Merely granting rights is insufficient if interfaces are permitted to neutralize them. Enforcement that focuses on how rights are presented, rather than whether they exist on paper, aligns more closely with observed consumer behavior.

Implications for Privacy Litigation

In private litigation, defendants frequently argue that consumers consented to data practices or could have avoided harm through diligence. The experimental evidence challenges both claims.

First, it demonstrates that consent obtained through manipulative interfaces may not reflect genuine agreement. Second, it shows that even diligent consumers fail when faced with systematically biased design. These findings weaken defenses premised on user fault or assumption of risk.

The identification of nagging as an independent dark pattern is particularly relevant to claims involving repeated consent requests or persistent prompts. Acceptance following repeated refusals may be better understood as acquiescence under pressure rather than voluntary choice.

For courts evaluating standing and injury, the study offers a way to conceptualize harm that does not depend on subjective distress. The harm lies in the predictable extraction of personal data contrary to consumer intent, facilitated by design.

What the Evidence Shows

The debate over dark patterns often turns on competing intuitions about consumer behavior. Proponents of self-help emphasize autonomy and choice; advocates of regulation emphasize manipulation and asymmetry. This study moves the debate from intuition to evidence.

The evidence shows that consumer self-help is not a reliable safeguard against privacy dark patterns. Even informed, motivated users routinely fail to protect their personal information when interfaces are designed to undermine their efforts.

At the same time, the findings demonstrate that consumers will exercise their rights when those rights are clearly presented. The failure, therefore, is not one of apathy, but of design.

This article does not prescribe a regulatory solution. It does, however, clarify the empirical landscape in which legal decisions must be made. When lawmakers, regulators, and courts assess the adequacy of consumer choice as a privacy protection, they should do so with a clear understanding of how choice actually functions in practice.

The question is no longer whether consumers could protect themselves in theory. The evidence shows that, in the presence of dark patterns, they generally cannot.